Design patterns: good practices and structured thinking

Every software developer has a desire to write better code. A desire to improve system performance. A desire to design software that is easy to maintain, easy to understand and explain.

Design patterns are recommendations and good practices accumulating knowledge of experienced programmers.

The highest level of experience contains the design guiding principles:

SOLID: Single Responsibility, Open/Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface

Segregation, Dependency Inversion

DRY: Don't Repeat Yourself

KISS: Keep It Simple, Stupid!

POLA: Principle of Least Astonishment

YAGNI: You Aren't Gonna Need It (overengineering)

POLP: Principle of Least Privilege

While these high-level concepts are intuitive, they are too general to give specific answers.

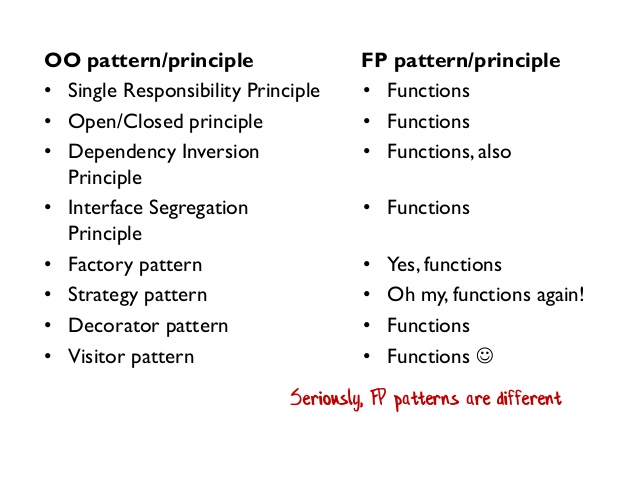

More detailed patterns arise for programming paradigms (declarative, imperative) with specific instances of functional or object-oriented programming.

The concept of design patterns originates in the OOP paradigm. OOP defines a strict way how to write software. Sometimes it is not clear how to squeeze real world problems into those rules. Cookbook for many practical situations

- Gamma, E., Johnson, R., Helm, R., Johnson, R. E., & Vlissides, J. (1995). Design patterns: elements of reusable object-oriented software. Pearson Deutschland GmbH.

Defining 23 design patterns in three categories. Became extremely popular.

(C) Scott Wlaschin

(C) Scott Wlaschin

Is julia OOP or FP? It is different from both, based on:

types system (polymorphic)

multiple dispatch (extending single dispatch of OOP)

functions as first class

decoupling of data and functions

macros

Any guidelines to solve real-world problems?

- Hands-On Design Patterns and Best Practices with Julia Proven solutions to common problems in software design for Julia 1.x Tom Kwong, CFA

Fundamental tradeoff: rules vs. freedom

freedom: in the C language it is possible to access assembler instructions, use pointer arithmetics:

it is possible to write extremely efficient code

it is easy to segfault, leak memory, etc.

rules: in strict languages (strict OOP, strict functional programming) you lose freedom for certain guarantees:

e.g. strict functional programming guarantees that the program provably terminates

operations that are simple e.g. in pointer arithmetics may become clumsy and inefficient in those strict rules.

the compiler can validate the rules and complain if the code does not comply with them.

Julia is again a dance between freedom and strict rules. It is more inclined to freedom. Provides few simple concepts that allow to construct design patterns common in other languages.

the language does not enforce too many formalisms (via keywords (interface, trait, etc.) but they can be

the compiler cannot check for correctness of these "patterns"

the user has a lot of freedom (and responsibility)

lots of features can be added by Julia packages (with various level of comfort)

- macros

Read:

Design Patterns of OOP from the Julia viewpoint

OOP is currently very popular concept (C++, Java, Python). It has strengths and weaknesses. The Julia authors tried to keep the strength and overcome weaknesses.

Key features of OOP:

Encapsulation

Inheritance

Polymorphism

Classical OOP languages define classes that bind processing functions to the data. Virtual methods are defined only for the attached methods of the classes.

Encapsulation

Refers to bundling of data with the methods that operate on that data, or the restricting of direct access to some of an object's components. Encapsulation is used to hide the values or state of a structured data object inside a class, preventing direct access to them by clients in a way that could expose hidden implementation details or violate state invariance maintained by the methods.

Making Julia to mimic OOP

There are many discussions how to make Julia to behave like an OOP. The best implementation to our knowledge is ObjectOriented

Encapsulation Advantage: Consistency and Validity

With fields of data structure freely accessible, the information may become inconsistent.

abstract type Plant end

mutable struct Grass <: Plant

id::Int

size::Int

max_size::Int

endWhat if I create Grass with larger size than max_size?

grass = Grass(1,50,5)Freedom over Rules. Maybe I would prefer to introduce some rules.

Some encapsulation may be handy keeping it consistent. Julia has inner constructor.

mutable struct Grass2 <: Plant

id::Int

size::Int

max_size::Int

Grass2(id,sz,msz) = sz > msz ? error("size can not be greater that max_size") : new(id,sz,msz)

endWhen defined, Julia does not provide the default outer constructor.

But fields are still accessible:

grass.size = 10000Recall that grass.size=1000 is a syntax of setproperty!(grass,:size,1000), which can be redefined:

function Base.setproperty!(obj::Grass, sym::Symbol, val)

if sym==:size

@assert val<=obj.max_size "size have to be lower than max_size!"

end

setfield!(obj,sym,val)

endFunction setfield! can not be overloaded.

Julia has partial encapsulation via a mechanism for consistency checks.

Array in imutable struct can be mutated

The mutability applies to the structure and not to encapsulated structures.

struct Foo

x::Float64

y::Vector{Float64}

z::Dict{Int,Int}

endIn the structure Foo, x cannot be mutated, but fields of y and key-value pairs of z can be mutated, because they are mutable containers. But I cannot replace y with a different Vector.

Encapsulation Disadvantage: the Expression Problem

Encapsulation limits the operations I can do with an object. Sometimes too much. Consider a matrix of methods/types(data-structures)

Consider an existing matrix of data and functions:

| data \ methods | find_food | eat! | grow! |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wolf | |||

| Sheep | |||

| Grass |

You have a good reason not to modify the original source (maintenance).

Imagine we want to extend the world to use new animals and new methods for all animals.

Object-oriented programming

classes are primary objects (hierarchy)

define animals as classes ( inheriting from abstract class)

adding a new animal is easy

adding a new method for all animals is hard (without modifying the original code)

Functional programming

functions are primary

define operations

find_food,eat!adding a new operation is easy

adding new data structure to existing operations is hard

Solutions:

multiple-dispatch = julia

open classes (monkey patching) = add methods to classes on the fly

visitor pattern = partial fix for OOP [extended visitor pattern using dynamic_cast]

Morale:

Julia does not enforces creation getters/setters by default (setproperty is mapped to setfield)

it provides tools to enforce access restriction if the user wants it.

can be used to imitate objects:

Polymorphism:

Polymorphism in OOP

Polymorphism is the method in an object-oriented programming language that performs different things as per the object’s class, which calls it. With Polymorphism, a message is sent to multiple class objects, and every object responds appropriately according to the properties of the class.

Example animals of different classes make different sounds. In Python:

class Sheep:

def __init__(self, energy, Denergy):

self.energy = energy

self.Denergy = Denergy

def make_sound(self):

print("Baa")

sheep.make_sound()

wolf.make_sound()Will make distinct sounds (baa, Howl).

Can we achieve this in Julia?

make_sound(::Sheep) = println("Baa")

make_sound(::Wolf) = println("Howl")Implementation of virtual methods

Virtual methods in OOP are typically implemented using Virtual Method Table, one for each class.

Julia has a single method table. Dispatch can be either static or dynamic (slow).

Freedom vs. Rules.

Duck typing is a type of polymorphism without static types

- more programming freedom, less formal guarantees

julia does not check if

make_soundexists for all animals. May result inMethodError. Responsibility of a programmer.- define

make_sound(A::AbstractAnimal)

- define

So far, the polymorphism coincides for OOP and julia because the method had only one argument => single argument dispatch.

Multiple dispatch is an extension of the classical first-argument-polymorphism of OOP, to all-argument polymorphism.

Challenge for OOP

How to code polymorphic behavior of interaction between two agents, e.g. an agent eating another agent in OOP?

Complicated.... You need a "design pattern" for it.

class Sheep(Animal):

energy: float = 4.0

denergy: float = 0.2

reprprob: float = 0.5

foodprob: float = 0.9

# hard, if not impossible to add behaviour for a new type of food

def eat(self, a: Agent, w: World):

if isinstance(a, Grass)

self.energy += a.size * self.denergy

a.size = 0

else:

raise ValueError(f"Sheep cannot eat {type(a).__name__}.")Consider an extension to:

Flower : easy

PoisonousGrass: harder

Simple in Julia:

eat!(w1::Sheep, a::Grass, w::World)=

eat!(w1::Sheep, a::Flower, w::World)=

eat!(w1::Sheep, a::PoisonousGrass, w::World)=Boiler-plate code can be automated by macros / meta programming.

Inheritance

Inheritance

Is the mechanism of basing one object or class upon another object (prototype-based inheritance) or class (class-based inheritance), retaining similar implementation. Deriving new classes (sub classes) from existing ones such as super class or base class and then forming them into a hierarchy of classes. In most class-based object-oriented languages, an object created through inheritance, a "child object", acquires all the properties and behaviors of the "parent object" , with the exception of: constructors, destructor, overloaded operators.

Most commonly, the sub-class inherits methods and the data.

For example, in python we can design a sheep with additional field. Think of a situation that we want to refine the reproduction procedure for sheeps by considering differences for male and female. We do not have information about gender in the original implementation.

In OOP, we can use inheritance.

class Sheep:

def __init__(self, energy, Denergy):

self.energy = energy

self.Denergy = Denergy

def make_sound(self):

print("Baa")

class SheepWithGender(Sheep):

def __init__(self, energy, Denergy,gender):

super().__init__(energy, Denergy)

self.gender = gender

# make_sound is inherited

# Can you do this in Julia?!Simple answer: NO, not exactly

Sheep has fields, is a concrete type, we cannot extend it.

- with modification of the original code, we can define AbstractSheep with subtypes Sheep and SheepWithGender.

But methods for AbstractAnimal works for sheeps! Is this inheritance?

Inheritance vs. Subtyping

Subtle difference:

subtyping = equality of interface

inheritance = reuse of implementation

In practice, subtyping reuse methods, not data fields.

We have seen this in Julia, using type hierarchy:

agent_step!(a::Animal, w::World)all animals subtype of

Animal"inherit" this method.

The type hierarchy is only one way of subtyping. Julia allows many variations, e.g. concatenating different parts of hierarchies via the Union{} type:

fancy_method(O::Union{Sheep,Grass}) = println("Fancy")Is this a good idea? It can be done completely Ad-hoc! Freedom over Rules.

There are very good use-cases:

- Missing values:

x::AbstractVector{<:Union{<:Number, Missing}}

SubTyping issues

With parametric types, unions and other construction, subtype resolution may become a complicated problem. Julia can even crash. Jan Vitek's Keynote at JuliaCon 2021

Sharing of data field via composition

Composition is also recommended in OOP: Composition over ingeritance

struct ⚥Sheep <: Animal

sheep::Sheep

sex::Symbol

endIf we want our new ⚥Sheep to behave like the original Sheep, we need to forward the corresponding methods.

eat!(a::⚥Sheep, b::Grass, w::World)=eat!(a.sheep, b, w)and all other methods. Routine work. Boring! The whole process can be automated using macros @forward from Lazy.jl.

Why so complicated? Wasn't the original inheritance tree structure better?

multiple inheritance:

you just compose two different "trees".

common example with ArmoredVehicle = Vehicle + Weapon

Do you think there is only one sensible inheritance tree?

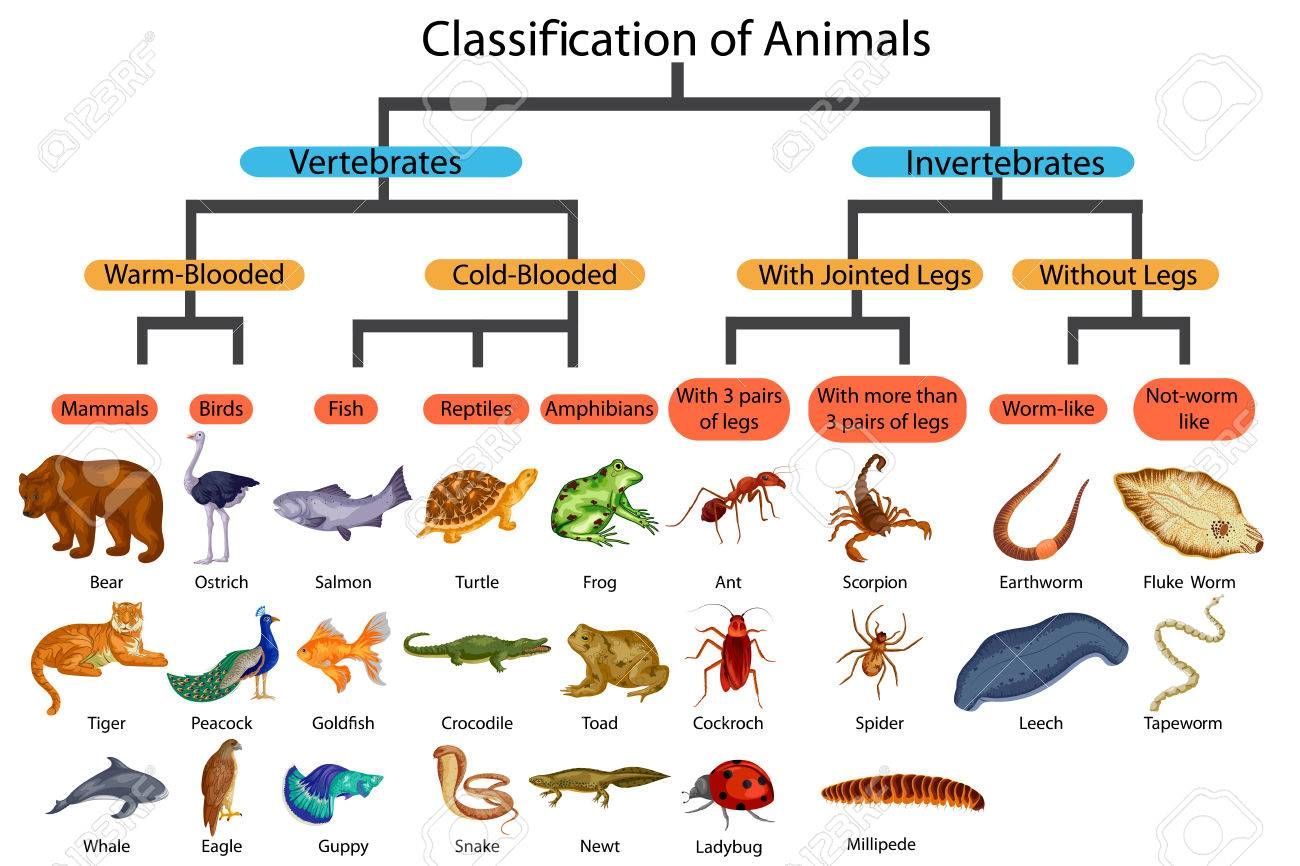

Animal World

Think of an inheritance tree of a full scope Animal world.

Idea #1: Split animals by biological taxonomy

Hold on.

Sharks and dolphins can swim very well!

Both bats and birds fly similarly!

Idea #2: Split by the way they move!

Idea #3: Split by way of ...

In fact, we do not have a tree, but more like a matrix/tensor:

| swims | flies | walks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| birds | penguin | eagle | kiwi |

| mammal | dolphin | bat | sheep, wolf |

| insect | backswimmer | fly | beetle |

Single type hierarchy will not work. Other approaches:

interfaces

parametric types

Analyze what features of animals are common and compose the animal:

abstract type HeatType end

abstract type MovementType end

abstract type ChildCare end

mutable struct Animal{H<:HeatType,M<:MovementType,C<:ChildCare}

id::Int

...

endNow, we can define methods dispatching on parameters of the main type.

Composition is simpler in such a general case. Composition over inheritance.

A simple example of parametric approach will be demonstarted in the lab.

Interfaces: inheritance/subtyping without a hierarchy tree

In OOP languages such as Java, interfaces have a dedicated keyword such that compiler can check correctness of the interface implementation.

In Julia, interfaces can be achieved by defining ordinary functions. Not so strict validation by the compiler as in other languages. Freedom...

Example: Iterators

Many fundamental objects can be iterated: Arrays, Tuples, Data collections...

They do not have any common "predecessor". They are almost "primitive" types.

they share just the property of being iterable

we do not want to modify them in any way

Example: of interface Iterators defined by "duck typing" via two functions.

| Required methods | Brief description |

|---|---|

| iterate(iter) | Returns either a tuple of the first item and initial state or nothing if empty |

| iterate(iter, state) | Returns either a tuple of the next item and next state or nothing if no items remain |

Defining these two methods for any object/collection C will make the following work:

for o in C

# do something

endThe compiler will not check if both functions exist.

If one is missing, it will complain about it when it needs it

The error message may be less informative than in the case of formal definition

Note:

even iterators may have different features: they can be finite or infinite

for finite iterators we can define useful functions (

collect)how to pass this information in an extensible way?

Poor solution: if statements.

function collect(iter)

if iter isa Tuple...

endThe compiler can do that for us.

Traits: cherry picking subtyping

Trait mechanism in Julia is build using the existing tools: Type System and Multiple Dispatch.

Traits have a few key parts:

Trait types: the different traits a type can have.

Trait function: what traits a type has.

Trait dispatch: using the traits.

From iterators:

# trait types:

abstract type IteratorSize end

struct SizeUnknown <: IteratorSize end

struct HasLength <: IteratorSize end

struct IsInfinite <: IteratorSize end

# Trait function: Input is a Type, output is a Type

IteratorSize(::Type{<:Tuple}) = HasLength()

IteratorSize(::Type) = HasLength() # HasLength is the default

# ...

# Trait dispatch

BitArray(itr) = gen_bitarray(IteratorSize(itr), itr)

gen_bitarray(isz::IteratorSize, itr) = gen_bitarray_from_itr(itr)

gen_bitarray(::IsInfinite, itr) = throw(ArgumentError("infinite-size iterable used in BitArray constructor"))What is needed to define for a new type that I want to iterate over?

Do you still miss inheritance in the OOP style?

Many packages automating this with more structure: Traitor.jl, SimpleTraits.jl, BinaryTraits.jl

Functional tools: Partial evaluation

It is common to create a new function which "just" specify some parameters.

_prod(x) = reduce(*,x)

_sum(x) = reduce(+,x)Functional tools: Closures

Closure (lexical closure, function closure)

A technique for implementing lexically scoped name binding in a language with first-class functions. Operationally, a closure is a record storing a function together with an environment.

originates in functional programming

now widespread in many common languages, Python, Matlab, etc..

memory management relies on garbage collector in general (can be optimized by compiler)

Example

function adder(x)

return y->x+y

endcreates a function that "closes" the argument x. Try: f=adder(5); f(3).

x = 30;

function adder()

return y->x+y

endcreates a function that "closes" variable x.

f = adder(10)

f(1)

g = adder()

g(1)Such function can be passed as an argument: together with the closed data.

Implementation of closures in julia: documentation

Closure is a record storing a function together with an environment. The environment is a mapping associating each free variable of the function (variables that are used locally, but defined in an enclosing scope) with the value or reference to which the name was bound when the closure was created.

function adder(x)

return y->x+y

endis lowered to (roughly):

struct ##1{T}

x::T

end

(_::##1)(y) = _.x + y

function adder(x)

return ##1(x)

endNote that the structure ##1 is not directly accessible. Try f.x and g.x.

Functor = Function-like structure

Each structure can have a method that is invoked when called as a function.

(_::Sheep)()= println("🐑")You can think of it as sheep.default_method().

Coding style

From Flux.jl:

function train!(loss, ps, data, opt; cb = () -> ())

ps = Params(ps)

cb = runall(cb)

@progress for d in data

gs = gradient(ps) do

loss(batchmemaybe(d)...)

end

update!(opt, ps, gs)

cb()

end

endIs this confusing? What can cb() do and what it can not?

Note that function train! does not have many local variables. The important ones are arguments, i.e. exist in the scope from which the function was invoked.

loss(x,y)=mse(model(x),y)

cb() = @info "training" loss(x,y)

train!(loss, ps, data, opt; cb=cb)Usage

Usage of closures:

callbacks: the function can also modify the enclosed variable.

abstraction: partial evaluation

Beware: Performance of captured variables

Inference of types may be difficult in closures: https://github.com/JuliaLang/julia/issues/15276